A blog of the Kennan Institute

BY VLADIMIR (ZE'EV) KHANIN

From the start, the Russian invasion of Ukraine instantly went beyond the level of subregional clashes to a restructuring of relations among the major world powers—the United States, the EU, Russia, and China. It has also greatly influenced relations among Middle Eastern countries, where it has triggered the strengthening of various geopolitical and strategic alliances.

One alliance in particular that has been bolstered is the Jerusalem-Baku partnership, which in recent years has become a full-fledged military-strategic alliance, with Azerbaijan emerging as Israel’s main energy supplier and source of intelligence about Iran and an important buyer of Israeli technology. As the swirl of unexpected consequences from the Russian-Ukrainian war engulfs region after region, this alliance is being pulled into the vortex and is turning into a de facto actor in the war.

What Is at Stake

From the time it first introduced a Russian military contingent into Syria in 2015 and continuing through the summer of 2022, Moscow has tried to maintain a balance of relations with Israel and Iran—an embodiment of what at the 2013 meeting of the Valdai Discussion Club was identified as the Kremlin’s version of a “balance-of-interests” doctrine, described as “standing in the Middle East on two legs.”

The understanding that was reached between Jerusalem and Moscow in that period included a relative freedom of action for the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) against Iranian and pro-Iranian forces in Syria and a suppression of arms supplies to Hezbollah and other Islamist groups, in exchange for Israel’s noninterference in Russian regional interests.

The Russian-Ukrainian war changed that arrangement. Large-scale losses have forced Russia to redeploy to the Ukrainian front some of its forces from Syria and the South Caucasus.

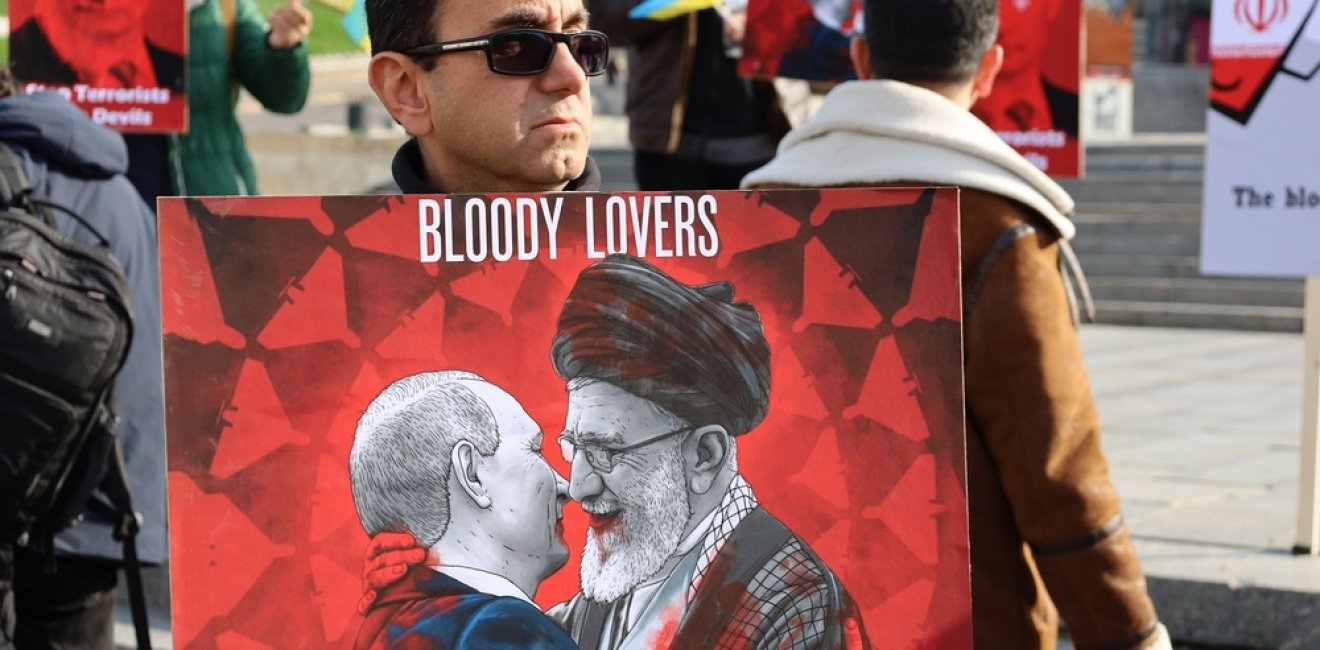

One actor ready to step into the vacuum left by Moscow’s partial withdrawal—with Moscow’s blessing—is Iran. The reported massive Iranian deliveries of drones, missiles, and engines needed to supply the Russian army testify to this change. If this is, in fact, a new trend, then it seems to suggest that Moscow is departing from its balance-of-interests approach in the Middle East and transitioning to a direct military-strategic alliance with Tehran.

The decline of the Russian deterrence of Iranian and pro-Iranian forces in Syria presents a danger to Israel and serves as a new source of difficulties. At the same time, it allows Israel more freedom of action—which, if media reports are to be believed, the IDF did not hesitate to take advantage of.

Second Front in the Caucasus

In Syria, Iran can do little to counter Israel and actions attributed to it, such as the targeted assassination of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps’ Sayyad Khodai, who served in the IRGC’s foreign operations unit. Instead, Iran could target another sensitive place for Israeli interests—the South Caucasus. Here, its prime goal would be an attempt to strike Azerbaijan.

Iran's motives here are clear. The rapidly developing economic and military Azerbajian-Israel partnership threatens Iranian interests. After recent complications, Israel’s relations with Turkey, Baku’s other strategic partner, are gradually warming up. (Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev has played a critical role in this reconciliation.)

Iran is also interested in filling the niche vacated by Russia in the demarcation zone between Azerbaijan and Armenia under the guise of protecting Armenia's interests, whose security Tehran recently declared it regards as “that of its own.”

Additionally, Iran wants to “take revenge” on Israel and to “warn” other regional actors from entering into a strategic partnership with Israel by inflicting maximum damage on Azerbaijan as a key ally of the Jewish state. In June, Iran mounted a campaign to glorify the imprisoned Muslim Unity movement head Taleh Bagirzade, presenting it as a response to the May 22 assassination of IRGC officer Hassan Khudayi by Mossad in Tehran and a series of similar Israeli operations that followed. The campaign ultimately led to conflicts within Iran's security services, as a result of which IRGC intelligence chief Hossein Tayyib was removed from his post.

Finally, Iran wants to dampen the ongoing antiregime demonstrations by mobilizing Iranian society against an “external enemy.” It is doing so by actively spreading propaganda that the unrest is the result of covert operations launched by Mossad from Azerbaijan. The media have been actively circulating statements to this effect by Iranian politicians, clergy, leaders of public organizations, and heads of security agencies.

On October 21 the commander of the Iranian Army, Abdulrahim Musavi, directly accused Israel and the United States of instigating mass disturbances by means of influencing the ethnic and religious minorities and youth. A statement issued by an unnamed intelligence officer claiming that Mossad was cooperating with other organizations in the region (a transparent hint at the intelligence agencies of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain) “in order to destabilize the Islamic Republic” was in a similar vein.

Declarations like these also seek to appeal to Iranians’ nationalistic feelings. In an October 21 statement by a high-ranking IRGC officer and addressed to Azerbaijan (which, the officer alleged, was “set to change borders to damage the routes of Iran's commercial ties with Europe”) reminded that country that in the past, its territories were part of the Persian Empire.

These statements were less intended to evoke media coverage in advance of future actions that Iran might take against Azerbaijan and Israel than they were an attempt to justify those actions after the fact. On October 17−19, large-scale IRGC exercises took place on the southern border of Azerbaijan, during which Iranian forces appeared to be just a step away from invading Azerbaijani territory.

During the IRGC maneuvers, Iranian TV channels broadcast statements to the effect that the maneuvers were aimed at Israel first and Azerbaijan second. The maneuvers, according to the U.S. Institute for the Study of War, were meant to show that Tehran would not tolerate “Israeli intelligence” on its border.

Plans for the Present

Two projects appear to be on Iran’s South Caucasus agenda today. The first is ripping away from Azerbaijan its autonomous exclave, the Nakhichevan, located directly to the north of the Iranian border. With this goal in mind, Iran foments ethnic and religious-sectarian separatism to try to destabilize the country from within and overthrow the “Zionist regime of Aliyev.”

On October 22 the Iranian army staged another exercise in the province of West Azerbaijan, during which it practiced airborne drops, night raids, and urban warfare. In parallel, numerous propaganda projects flooded social and conventional media, mobilizing supporters for the transition of Nakhichevan to Iranian control. For example, on October 21 the Telegram channel İranın Naxçıvani Xalq Hərəkatı declared, in the name of the previously unknown Iranian Nakhchivan People's Movement, that “the dream of the people of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic is to become part of the Islamic Republic of Iran.”

The Iranian Azerbaijani language propaganda channel Səhər Azəri announced “the formation of a popular movement for the return of Nakhchivan to Iran.” And channels such as MiranPress have been broadcasting propaganda claiming that Nakhchivan residents have grown weary of “racial discrimination” and wish to “return to Iran.”

The matter is not limited to Nakhichevan, however. There is evidence of attempts to stir separatism among the Talysh people in southern Azerbaijan—in this case, in favor of Russia. For instance, an appeal by an anonymous Avar activist, published on a separatist Tolish Media website, calls on the “Russian world” to support the independence of the “Dagestan peoples”—Lezgin and Avars—living in the northeast and northwest of Azerbaijan. These actions must also be viewed as an effort to frustrate the Baku-Ankara plans to create a Zangezur corridor through Armenia’s territory that would connect Azerbaijan and Turkey.

There is no denying the authoritarian nature of Ilham Aliyev’s regime and its problematic human rights record. On the other hand, not a few of Aliyev’s critics and opponents ostensibly use a human rights umbrella to promote radical Khomeinist agenda in the secularist Azerbaijan. Over the past two decades, Azerbaijan has consistently made pro-Western foreign policy choices. It has demonstrated impressive economic growth and built stable diplomatic relations with regional and global powers while avoiding, more or less successfully, explosions of separatism. Most recently, it has offered itself as a solution to Europe’s energy crisis. The changes engendered by the launching of Russia’s war on Ukraine are now posing hard challenges to its stability, and possibly even survival, ginned up by the Iranian regime.

Critics of the current Azerbaijani leadership often argue that the Iranian threat could have been avoided had Aliyev’s government toned down its strategic partnership with Israel. But that country's leadership doesn’t share that perspective. It seems that, similar to Israel’s new Abraham Accords’ Arab partners, Azerbaijan views an alliance with Israel as a solution to its problems, not their cause.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Middle East Program

The Wilson Center’s Middle East Program serves as a crucial resource for the policymaking community and beyond, providing analyses and research that helps inform US foreign policymaking, stimulates public debate, and expands knowledge about issues in the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

A World Ready for Realignment?

Staging Crime and Punishment, a Ballet of Our Times

The Human Tragedy of War