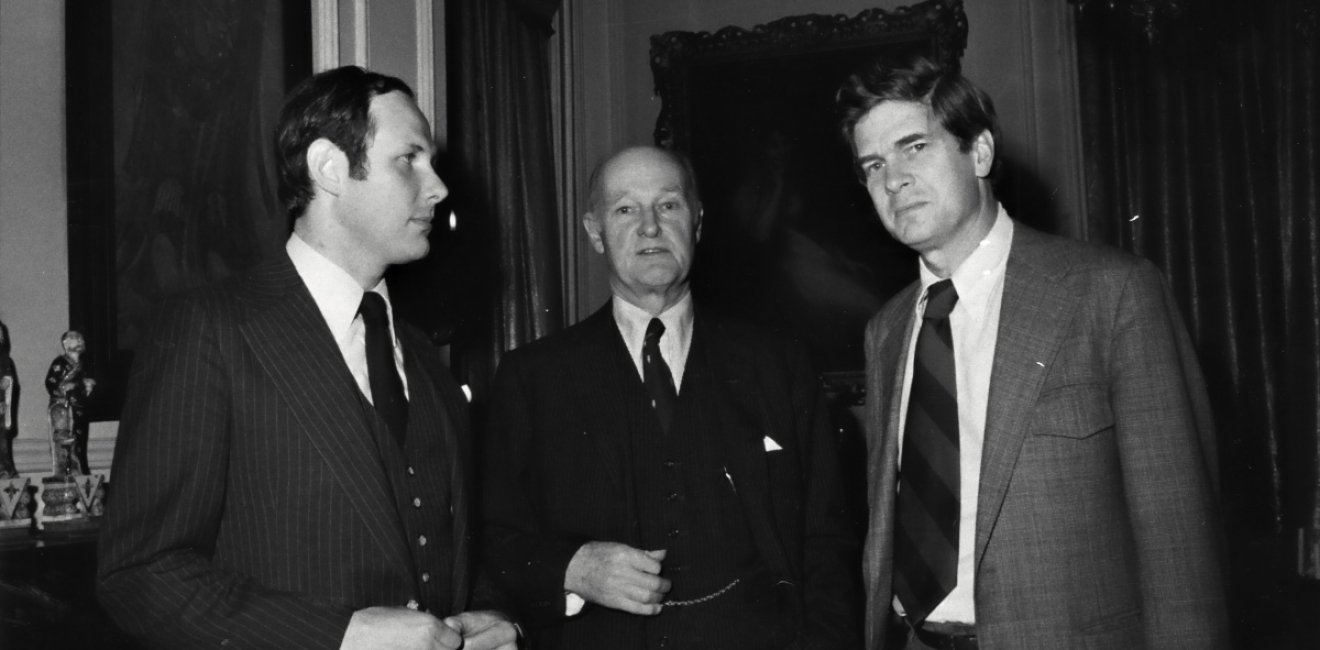

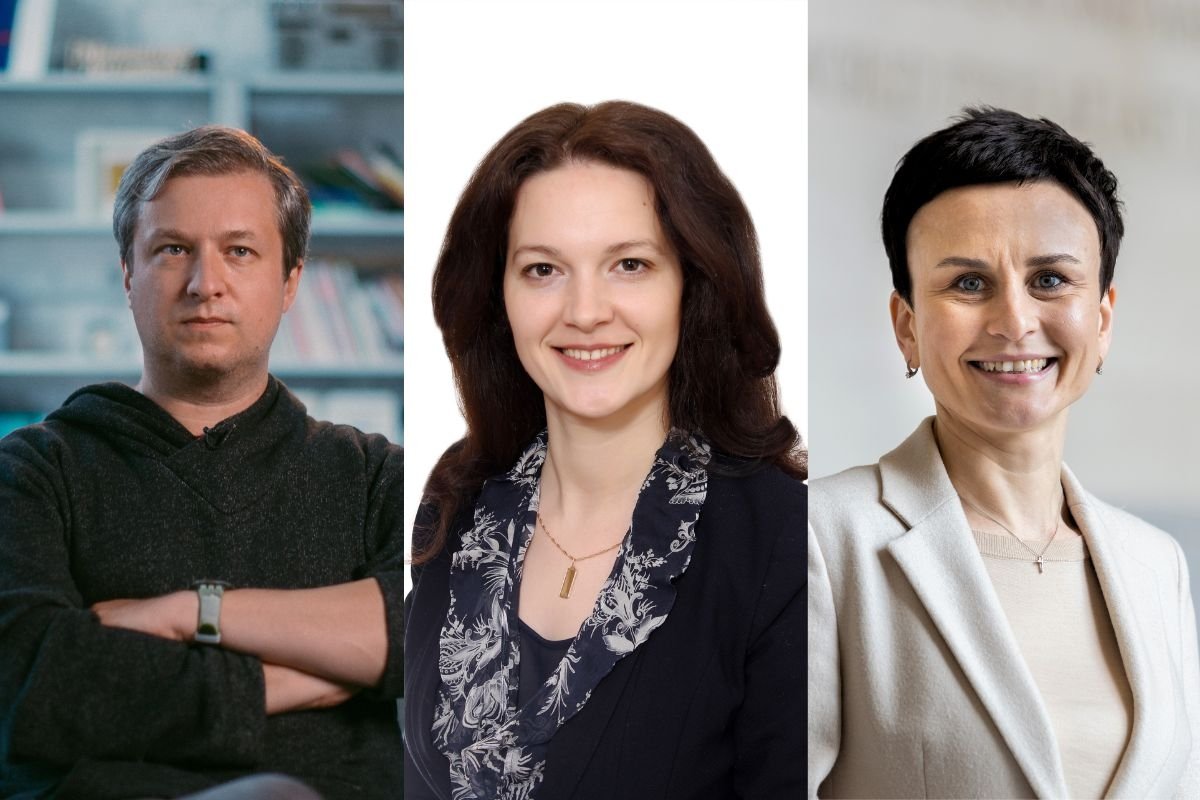

Jill Dougherty

Dougherty (top left) is a renowned expert on Russia and Eurasia, Global Fellow at the Wilson Center, host of the KennanX podcast, and Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University’s Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies. She held many posts during her three-decade career with CNN, including the White House Correspondent and the Moscow Bureau Chief, and continues to provide reporting and analysis on Russia and related issues as a CNN on-air Contributor.

Andrei Kozyrev

Kozyrev (top center) is the former Foreign Minister of the Russian Federation, an expert on Russian politics and international affairs, and the author of The Firebird: The Elusive Fate of Russian Democracy. As post-Soviet Russia’s first Foreign Minister, he participated in negotiations to peacefully dissolve the Soviet Union and advocated for improved relations with the West. After leaving the ministry and serving in the Russian State Duma for two terms, he resigned from politics and pursued a career in business.

Chris Miller

Miller (top right) is a Professor of International History at the Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, co-director of Fletcher's Russia and Eurasia Program, and a Senior Fellow with the Foreign Policy Research Institute’s Eurasia Program. He has conducted research on technology, geopolitics, economics, and international affairs, and is the author of four books, including the New York Times bestseller Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, which won the Financial Times Business Book of the Year Award and the Council on Foreign Relations Arthur Ross Book Award.

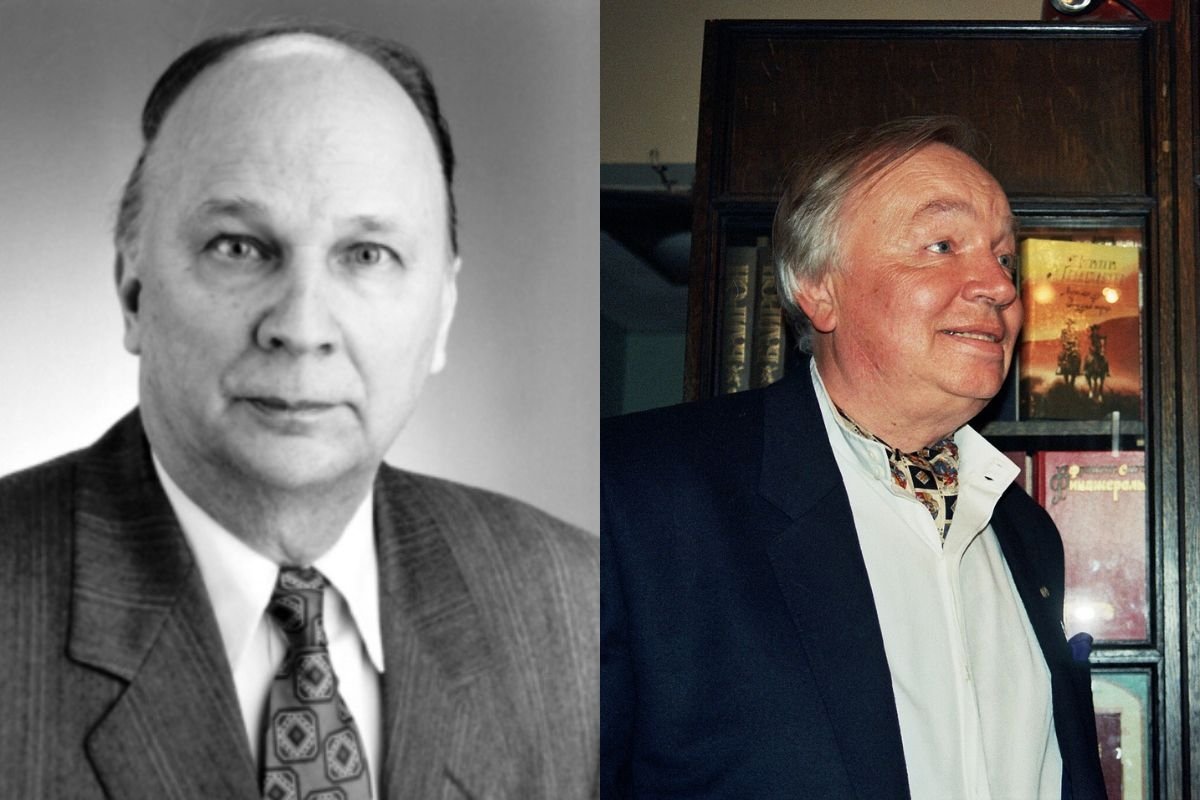

Kirill Rogov

Rogov (bottom right) is a prominent political analyst and columnist and a Visiting Researcher at the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) in Vienna. He is also the founder and director of Re: Russia Project, an expert and discussion platform publishing insights on Russian politics, economy, and society. He is the co-founder and former chief editor of Polit.ru and former leading researcher at the Gaidar Institute in Moscow, who is frequently quoted by the Economist, the New York Times, and the Washington Post.

Maria Stepanova

Stepanova (bottom center) is a poet, essayist, and journalist. She is the founder and editor-in-chief of Colta.ru, an independent online publication covering Russian culture and society. Her poems and prose have been translated into many languages, and she has received multiple Russian and international literary awards, including the 2023 Leipzig Book Prize for European Understanding for her poetry collection Girls without Clothes. Her book, In Memory of Memory, “a multifaceted essay on the nature of remembering,” was shortlisted for the 2021 International Booker Prize.

Elizabeth A. Wood

Wood (bottom left) is the Ford International Professor of History at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, founding director of the MIT Ukraine Program, co-director of the MIT-Eurasia Program, and Coordinator of Russian Studies. She serves as the Vice-Chair of the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research (NCEEER) and has written three books and numerous scholarly articles, including Roots of Russia’s War in Ukraine and The Baba and the Comrade: Gender and Politics in Revolutionary Russia.