This article is part of a series of papers that resulted in the new report:

First Resort: An Agenda for the United States and the European Union

The past decade has been akin to a roller-coaster ride for EU-US relations. The launch of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership in 2013, arguably the peak of the two superpowers’ willingness to cooperate and integrate their economies, ended up in a stalemate already in 2016, and hit a wall when the Trump administration took office. The ongoing Brexit process (hailed by Donald Trump as a “great victory”) seems to have further undermined the solidity of a relationship that was for seven decades the main pillar of the post-World War II international order. And the COVID-19 pandemic seems to be further challenging a relationship that is seen as ”already damaged” (Brattberg 2020). At the same time, towards the end of 2020 the need for a new transatlantic agenda was highlighted by several leaders, including the President of the European Commission Ursula Von der Leyen and US State Secretary Mike Pompeo. The election of Joe Biden is likely to bring new lymph to the relationship between the two powers: the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen welcomed the result of the election and stated the willingness to intensify cooperation, i.a. on “promoting a digital transformation that benefits people”. On 2 December 2020, a series of proposals for “a new transatlantic agenda for global change” was published by the European Commission in a Joint Communication with the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (hereinafter, the “Joint Communication”), containing concrete proposals: to establish a new EU-US Trade and Technology Council; to create a specific dialogue on the responsibility of online platforms and Big Tech; to work together on fair taxation and market distortions; and to develop a common approach to critical technologies including Artificial Intelligence, data flows, and cooperation on regulation and standards.

In reality, agreement on these proposals will depend on the convergence of interests between the two blocs. As a matter of fact, nowhere are the ups and downs of transatlantic relations more visible than in digital innovation and policy. Over the past decade, transatlantic relations have navigated difficult waters due to divergences in important policy domains such as data protection and antitrust law; the debate on the web tax and the ex ante regulation of digital platforms; difficulties over the US ban on Huawei, which European countries decided to only partly emulate; and Europe’s ambition to strengthen its technological sovereignty, which aims i.a. to reduce Europe’s dependence on large US-based cloud operators. European politicians often lamented that Europe has become a “digital colony” of the US, mostly thanks to the widespread presence of American tech giants in the continent.

The technology stack: no country can “go it alone”

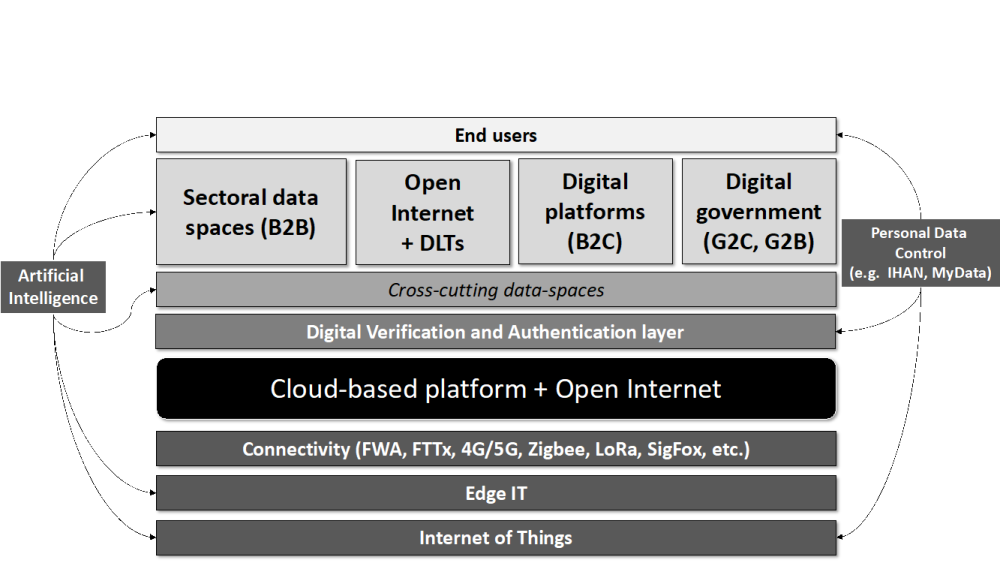

An appropriate way to look at the terrain of US-EU cooperation is to observe the full digital technology stack, as depicted in the figure below.

The evolving digital technology stack

Internet experts have traditionally considered the digital ecosystem to comprise four main layers: (i) a physical layer, which includes connectivity (wireline and wireless, including 5G and other emerging protocols), computing capacity, semiconductors and connected devices, also defined as the Internet of Things (IoT); (ii) a logical layer, which contains the main protocols for data flows and exchanges, as well as digital authentication and verification protocols; (iii) a platform layer, which includes B2C but also B2B and G2C platforms supporting applications; and (iv) an application layer, in which services and products are provided to end users in a way that is compatible with the underlying platforms. These layers are evolving with a growing level of complexity: the physical layer is enriched by a variety of connectivity options and the blossoming Edge/IoT layer; the platform layer is becoming less predominant and is increasingly flanked by coordinated data spaces, especially for industrial and government use cases; the application layer is increasingly rich and dependent on the underlying platforms; and the logical layer is increasingly incorporating legal and semantic interoperability, as well as digital authentication and verification protocols. Importantly, in this context Artificial Intelligence is not a layer, but rather a set of techniques that permeate all the layers of the technology stack.

When looking at the full technology stack, it emerges clearly that at present no superpower can claim to be self-sufficient. China currently does not have the capacity to produce state-of-the-art semiconductors and is in fact dependent on advanced chips from the US. Other than this, China appears rather self-sufficient in the provision of infrastructure, platforms, and applications, and runs its own “great firewall”, de facto altering the openness of the Internet on its own territory. At the same time, the US, traditionally a leader on digital technology, appears to significantly lag behind both the EU and China in a specific area, 5G, which is key for future applications of AI, both in the consumer and in the industrial domain. In this context, Europe lacks well-developed platforms, and is dependent on other countries for semiconductors, as well as (partly) for 5G connectivity.

Paths towards exploiting synergies and defending democracy

The lack of self-sufficiency of all players offers an interesting perspective on on-going strategies in the broader digital space. Thus, if the US prioritised actions aimed at slowing down China’s rise in this domain, for example by banning Huawei from the US market (and beyond), this would come with a cost in terms of a delayed rollout of 5G at the domestic level. These restrictions are also bound to have a negative impact on US semiconductor firms, many of which make large revenues in the Chinese market (Ernst 2020). And in turn, they would harm the technological environment in which future AI applications are emerging. Accordingly, full-fledged technological sovereignty does not seem to be a suitable option for the US in the broader technology space. Similarly, pursuing full technological sovereignty would condemn Europe to a significant slowdown in the digital transformation. Not only have many European Member States accumulated delays in deploying both fixed and mobile infrastructure; Europe also lacks large-scale digital platforms and is home to a small, albeit vibrant, application economy compared to the US and China. And even in 5G, despite the fact that Nokia and Ericsson hold significant shares of the essential patents, technological complementarity is such that Europe appears far from independent: for example, in Germany mobile operators recently estimated that the exclusion of Huawei from 5G deployment would cost an additional 50 billion and cause significant delays.

The analysis of the technology stack unveils important opportunities in terms of exploiting complementarities to achieve self-sufficiency, or even transatlantic autonomy. The most evident of these complementarities is given by Europe’s relative underdevelopment in the higher layers (AI, platforms) of the stack, and stronger positioning in key parts of the lower layer (5G) compared to the US. In principle, the United States could offer its European counterparts enhanced access to its domestic 5G market, in exchange for more cooperation, and perhaps regulatory convergence, on the side of platforms and AI. Rational players would probably consider this cooperation to be Pareto-efficient. And indeed, recent events, from declarations of interest by the US in investing in Nokia or Ericsson to European Commission Vice President Vestager’s call for transatlantic convergence in platform regulation, broadly support this view.

Against this backdrop, key areas for enhanced cooperation could include the following:

- Wireless broadband. European companies such as Nokia and Ericsson, who jointly represent 25% of the Standard Essential Patents, could step up cooperation with American companies like Qualcomm, to boost deployment of 5G and develop standards and technologies for the 6G era, on which research and development has already started.

- Artificial Intelligence. Besides cooperating in the context of the Global Partnership on AI, as well as in the G7 and G20, the US and the EU could join forces to boost R&D on AI applications and techniques that are compatible with users’ rights to data protection and privacy (e.g. federated machine learning); as well as on “AI for good” (e.g. in AI applications oriented towards sustainable development, including climate policy). Cooperation on AI is possible also in key regulatory areas such as risk classification and responsible AI development, especially in view of the recent Memoranda adopted by the US administration, as well as the forthcoming EU AI regulation to be proposed by the European Commission in the first quarter of 2021. Alignment on conformity assessment, risk classification and mitigation approaches could foster the creation of a transatlantic market for certified, audited AI products, which in turn could boost trade and integration between the two blocs, as well as with other countries (e.g. Canada, the UK). However, a key precondition for enhanced cooperation would be an attempt to cross the existing chasm between the US’ mostly sectoral and rather minimalistic approach, and the EU’s horizontal and rather far-reaching approach to AI regulation.

- Data governance and flows. Governance of data flows has become a pillar of the EU’s new digital strategy aimed at technological sovereignty. Assuming that sovereignty is not interpreted and implemented as outright protectionism, but purely as the legitimate aim to reduce dependency on non-domestic technology, the US and the EU could then give rise to intense cooperation on ensuring reciprocal access to data spaces, in particular the ones related to key verticals (healthcare, agriculture, manufacturing), as well as to the emerging EU data space for the Green Deal. Maximising the quantity and quality of data available for key machine learning applications “for good” could be an important pathway for enhance transatlantic cooperation. In terms of personal data flows, much will depend on the evolution of the EU “federated cloud” project, based on the GAIA-X Franco-German initiative, which will incorporate GDPR compliance “by design”. Ensuring that such compliance can be easily achieved also for non-EU companies may facilitate future adequacy negotiations in the field of data protection, which will move from the legal terrain from a more technological one. The Joint Communication of 2 December 2020 proposes the development of a transatlantic AI Agreement and an intensified cooperation to facilitate free data flow with trust.

- Digital taxation. The European Commission, pushed i.a. by France and Italy, is determined to move in the direction of imposing a digital tax regardless of the outcome of the OECD process in this domain. This issued seems to have become more widely acknowledged also as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which accelerated the transition of several markets towards full digitisation, thereby favouring digital platforms over traditional players. The taxation dossier may require a more in-depth discussion on where profits and revenues should be taxed, and where value is actually created. Past divergence between the two administrations, e.g. in the case of European Commission v. Ireland, may stand in the way of enhanced cooperation.

- Platform regulation and antitrust law. Administration on both sides of the Atlantic are showing an increased attitude towards developing a regulatory framework for platforms. In the US, the debate on the creation of an authority in charge of platform regulation has produced first proposals. In the EU, this debate is more mature, also thanks to an approach to competition policy that has traditionally been more focused on market structure and the preservation of entry possibilities for smaller firms. As a matter of fact, the recent Platform to Business (P2B) regulation and the forthcoming proposals for a Digital Markets Act echo pre-existing legislation at the national level in several EU Member States, focused on situations of abuse of economic dependency, abuse of superior bargaining power, and other cases of unfair trading practices. Besides those regulatory approaches, as already mentioned, antitrust rules are being revisited in Europe, in view of a possible departure from traditional concepts such as abuse of dominance. Upcoming European proposals, including the “new competition tool” expected in 2021, move in the direction of tackling specific cases of “gatekeeping” or “intermediation power”, which would allow the imposition of remedies even in the absence of proven abuses of market power. The approaches in the US and the EU remain rather different in this space: however, the EU Joint Communication calls for “a new transatlantic dialogue on the responsibility of online platforms, which would set the blueprint for other democracies facing the same challenges”; and a stronger “cooperation between competent authorities for antitrust enforcement in digital markets”.

- Online content and the protection of democracy. A shared interest on both sides of the Atlantic is the protection of the democratic process, including i.a. tackling disinformation and specific emerging practices such as deepfakes. This shared objective could also be part of a dialogue on the responsibility of platforms for content moderation and algorithmic take-down of hate speech and fake news, which would benefit from a coordinated transatlantic approach. Such a coordinated approach would also achieve more effective results at the global level, addressing situations in which authoritarian regimes weaken or disregard the protection of human rights, and hard-to-attribute cyber-attacks threaten to subvert or destabilise democracy.

- Cybersecurity and overall tech governance. Data-sharing and mutual assistance for real-time responsiveness to cyber-threats will be increasingly essential in a world characterised by the growing use of sophisticated AI to penetrate often vulnerable systems. Experts have regularly highlighted that AI/IoT systems still feature a high degree of vulnerability and an ever-denser “attack surface”: a coordinated approach to strengthening the resilience of critical infrastructure would significantly benefit the transatlantic economy. The US and the EU could also be an engine of transition from the world of “openness at all costs”, towards the creation of a trusted infrastructure that reduces exposure to external attacks, at least for critical data flows.

- Standardization and Internet governance. Future transatlantic cooperation could be also oriented towards avoiding the fragmentation of Internet governance and architectures, as in the oft-evoked scenario of the “splinternet”. Maintaining a global dialogue with all players, including authoritarian regimes, is an essential ingredient for a prosperous and stable future society. That said, positions expressed by Chinese companies, invoking changes in the Internet Protocol to account for the massive development of the Internet of things and extended reality, deserves careful consideration as it touches upon a concrete, existing problem in the governance of the future Internet.

- Research and development. On all the areas above, stronger integration of R&D programs would be extremely important. This could take several forms, for example allowing the funding of foreign players in research programmes such as the ones run by NSF in the US, and the Horizon Europe programme in the EU; but also, importantly, launching “moonshots” to address key global challenges, including i.a. brain and cancer research, as well as climate-related research.

All these areas are potential candidates for a stronger and more coordinated transatlantic economy. A window of opportunity seems to exist after the US elections, also due to the emerging awareness of the need to strengthen the regulatory framework to ensure that digital technologies continue to provide a positive contribution to the economy, society, and the environment. Time will tell whether the diverging starting points, and the different “BATNAs” (“best alternative to the negotiated agreement”) of the US and the EU in this space will stand in the way of an otherwise fruitful season of cooperation.

Author

Global Europe Program

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe”—an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more